This was the second meeting in a series of three about food supply resilience, and we used examples provided by the witnesses to explore ways in which overlaying big data sets and remote sensing can assess and communicate risk and resilience in food supplies and changes in biodiversity.

Our first witness was Dr Francois Kayitakire, a senior scientist at the Joint Research Center (JRC) in the Institute of Environment and Sustainability (IES) based in Ispra, Italy. He leads a team working on resilience and on food and nutrition security assessment within the Food Security (FOODSEC) Group which focuses on resilience measurement issues, food security assessment and classification methods, and on agricultural risk management in developing countries.

He joined Dr Matthew Smith, an ecologist working in the Computational Science Lab at Microsoft Research whose research focuses on demonstrating how the deployment of valuable new environmental information can benefit businesses and society. He also maintains research interests in predicting crop dynamics, carbon and vegetation, human responses to climate change, and ecosystem structure and function.

Our third witness was Craig Mills, the CEO of Vizzuality, a science and technology company focused on data visualization, web-GIS and tool development and committed to working on projects related to conservation, the environment and sustainable development. Current projects related to our topic include developing a new way to visualise forest data for the World Resources Institute and a joint research project with the Zeitz Foundation to explore how to use satellite data and mobile phones to help small scale farmers in Kenya improve their food productivity.

Wicked problems and questions generated by the discussion

How do we build resilient food systems in both developing and developed countries?

The politics of data are very complex and can be politically changed and politically sensitive which will influence both how the data are collected and how it is used.

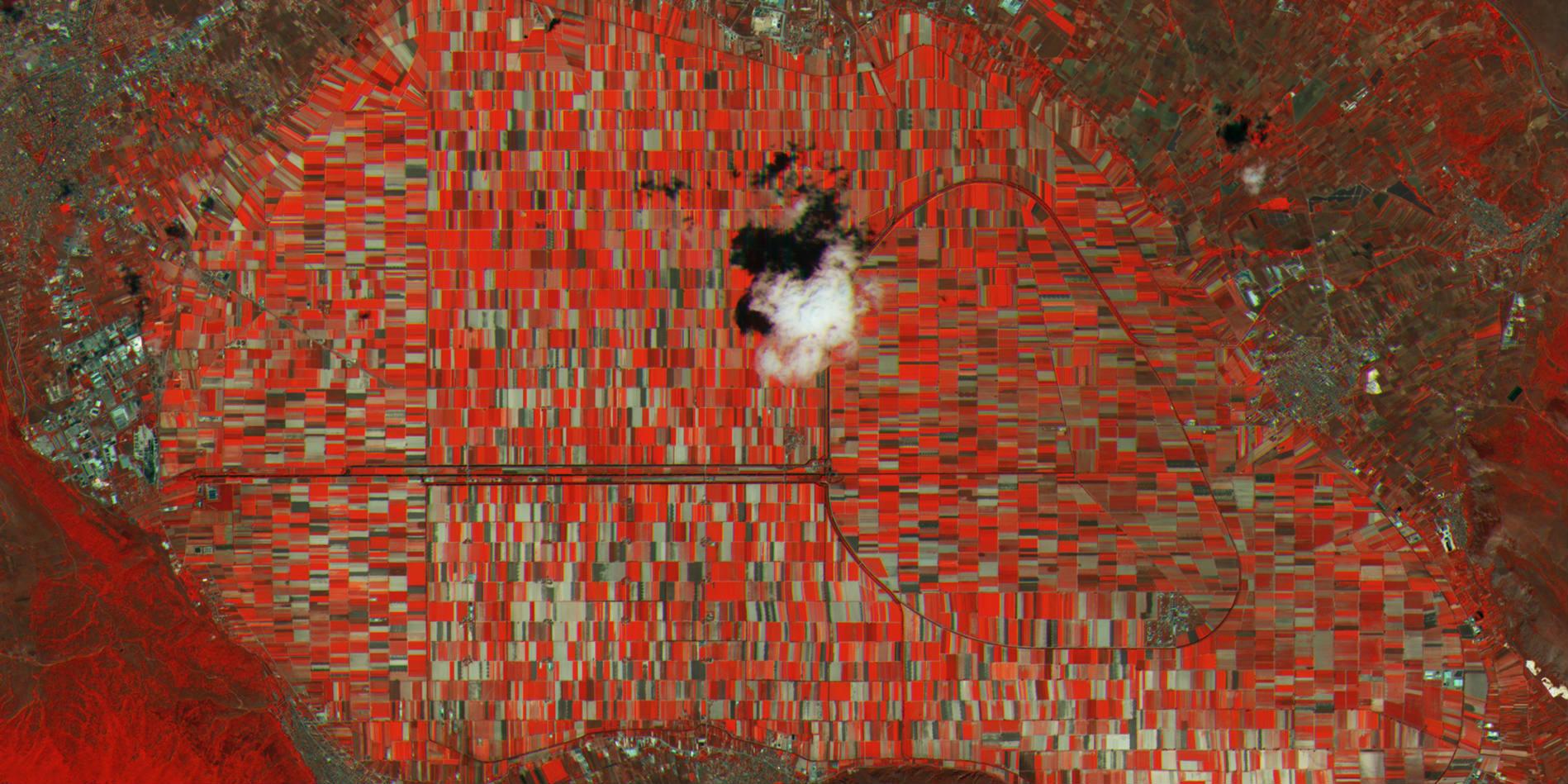

Bringing remote sensing data down to a human scale: There is a disconnect between environmental information and people’s understanding and use of that information. There are many new opportunities for open data and services, such as Copernicus, but as yet, there has been relatively little investment in how to communicate the information in a way that people can use to make decisions in the real world.

Remotely sensed data does not replace the need for on the ground sensors and information, but instead compliments it. Finding ways to be able to support long term, ground and air based datasets will be an essential part of answering the questions we need to ask about food security in the future.

Decisions are taken at multiple scales from local to international. What place does satellite data have in decision-making at all of these scales and is it feasible to use it to make local scale decisions?

Is there scope for a growing role for citizen science in this ‘new world’ of open, big data?

Although boring, data collection and storage standards are going to become increasingly important if we are going to be able to be able to cross-analyse and layer different datasets. Could lessons to be learnt from the experience of genetic open data be applied to environmental datasets?

For more information about these meetings, please follow the links on the right or e-mail Dr Rosamunde Almond (r.almond@damtp.cam.ac.uk)